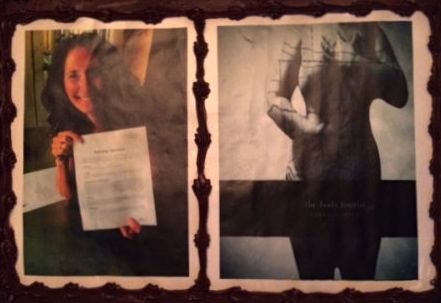

My memoir, The Body Tourist, was published in November, 2014 by Little Feather Books, a small, independent publishing house in NYC. Soon afterward, my good friends Frank and Carol White had a congratulations party for me, complete with a feather centerpiece (get it? Little Feather Books? Feather centerpiece?), basil-infused gin and tonics, and a chocolate cake with images–printed in sugar–of me holding the signed contract, and the book cover (see picture, left). It was truly one of the most creative and amazing and thoughtful things anyone has ever done for me. Thirty-five of my closest friends were there, and while they all knew I’ve been working on the book for many years, and knew basically what it’s about (the 6 years following my so-called recovery from anorexia), I wanted to give them a bit more about the book without giving a formal reading, and I wanted it to be quick so as not to disrupt the party’s energy. So before the party I went through the manuscript and picked one line from each of the 34 chapters of the book. Saturday night, just before we dove into the cake and basil-infused gin & tonics, I read the lines aloud in quick succession. If you weren’t there and you’d like a flavor of The Body Tourist without the time commitment, here it is:

My memoir, The Body Tourist, was published in November, 2014 by Little Feather Books, a small, independent publishing house in NYC. Soon afterward, my good friends Frank and Carol White had a congratulations party for me, complete with a feather centerpiece (get it? Little Feather Books? Feather centerpiece?), basil-infused gin and tonics, and a chocolate cake with images–printed in sugar–of me holding the signed contract, and the book cover (see picture, left). It was truly one of the most creative and amazing and thoughtful things anyone has ever done for me. Thirty-five of my closest friends were there, and while they all knew I’ve been working on the book for many years, and knew basically what it’s about (the 6 years following my so-called recovery from anorexia), I wanted to give them a bit more about the book without giving a formal reading, and I wanted it to be quick so as not to disrupt the party’s energy. So before the party I went through the manuscript and picked one line from each of the 34 chapters of the book. Saturday night, just before we dove into the cake and basil-infused gin & tonics, I read the lines aloud in quick succession. If you weren’t there and you’d like a flavor of The Body Tourist without the time commitment, here it is:

The Body Tourist In 34 Lines

Chapter 1

“We’ve been robbed,” my mother says.

Chapter 2

I sit down and hand him my resume which suggests, by omission, that I attended not three colleges but only the one that conferred my degree, and which lovingly details a six-month internship at the state hospital but says nothing about my collection of lost jobs.

Chapter 3

Rage in all its forms–impotent, seething, weepy, diabolical–was her only recourse.

Chapter 4

To the observer I look like any new employee taking in the information about her duties—but behind the scenes, my heart is acting out a tragic drama in articulate palpitations.

Chapter 5

Linda’s bifurcated world of puking and fucking is already beginning to wear on me, and I’ve known her for less than an hour.

Chapter 6

“It smells like a train station in here.”

Chapter 7

He winks.

Chapter 8

My peers’ outward accoutrements of sophistication paled in the face of my American boy and our king-size box of condoms.

Chapter 9

It’s a proven fact that everything that happens to an addict is someone else’s fault.

Chapter 10

I was in love—not with freckled, butterfly-loving, ten year-old Richie, but with the troubled boy-man with the mysterious, brooding core, the Richie undone by his own father, the bewildered, betrayed Richie who, in the moment before he died, might have looked up from the hole in his chest with a mix of apology and incomprehension.

Chapter 11

“Do not fuck him.

Chapter 12

I am vaguely aware of being angry now at my own anger, and doubly angry with my father for making me have to be mad at myself.

Chapter 13

At the heart of my predicament is the relationship I have developed with my illness: the love affair I have with feeling in exquisite control of my appetite, and the reprieve I feel in focusing on food instead of the real issues—my loneliness for example, my many fears, and now, my father’s illness.

Chapter 14

A lifetime of sickness and management, an incalculable madness that began as a benign thrumming in his chest and translated to the malignant rattle of pills in his pocket, ceases, with a profusion of tumors in his bladder, to exist.

Chapter 15

We groped.

Chapter 16

‘Up and coming’ is a euphemism for ‘down and out,’ my mother says.

Chapter 17

Something in me is fumbling toward a larger realization that has to do with my mother and my mother’s mother, with the kinds of loss that pull us up and away, out of the warm lake of childhood and into the dry, cool lap of a world we won’t fully understand until we are older.

Chapter 18

Patti holds the baby out to me and I do not reach for it.

Chapter 19

“You might not make friends easily, but I do.”

“Chapter 20

“It’s a long story,” I say, although it really isn’t any longer than “sex.”

Chapter 21

The fact is, unless I am a social worker or a probation officer, I have no business being in this North Augusta neighborhood, and so I move in.

Chapter 22

The area that presently concerns me is the narrow strip of terrain between my navel and my crotch, the gentle female swell whose existence I have always believed I must nullify in order to be found praiseworthy and desirable.

Chapter 23

“I don’t want to be happier!” I yell.

Chapter 24

I have only to do this simple thing—decline Austin’s hand in marriage—to set myself free.

Chapter 25

Wouldn’t it be funny if I fell from a balcony onto a freeway?

Chapter 26

Blind certainty believes, utterly and wholly, in itself.

Chapter 27

Beside me in the passenger seat my paycheck lies open and smoothed flat, and every few seconds I look over at it admiringly like it is a new baby.

Chapter 28

It certainly does not occur to me to consider that Fisher, unable to dress properly or cook for himself, might, like the house itself, have good bones but cavernous deficiencies.

Chapter 29

“I just know how sneaky Jesus can be,” I say.

Chapter 30

On the test, I claimed that my father was a good man and that I had never stolen from my workplace.

Chapter 31

And then I remember: my father had an alias.

Chapter 32

His face, while handsome, lacks the deeply etched crease I so loved in Fisher’s, evidence (I believed) of profound thought, which left its mark on especially reflective men.

Chapter 33

Barukh ata Adonai Eloheinu Melekh ha‑olam, bo’re p’ri ha‑gafen.

Chapter 34

I have a recurring dream about a house.

THE END